I have a confession to make. Until a couple of years, I couldn’t care less about Beaujolais. The earliest memory I have of drinking Beaujolais was in 2006 when I was studying in Japan.All of a sudden the local supermarket, which never offered anything non-Japanese in terms of alcohol, was stocked with rows and rows of Beaujolais Nouveau. Little did I know then what type of wine it was, why it was such a hype and where exactly it came from, but it was cheap, available in huge quantities and so sweet that the sugar would keep you wide awake throughout your hangover. When I got back to Belgium the next year and started following a generic wine class, Beaujolais was never really mentioned in a positive way. It always came across as the region that had its chance at success but never got it quite right, ruined by quick gains and a marketing machine in overdrive.

I have a confession to make. Until a couple of years, I couldn’t care less about Beaujolais. The earliest memory I have of drinking Beaujolais was in 2006 when I was studying in Japan.All of a sudden the local supermarket, which never offered anything non-Japanese in terms of alcohol, was stocked with rows and rows of Beaujolais Nouveau. Little did I know then what type of wine it was, why it was such a hype and where exactly it came from, but it was cheap, available in huge quantities and so sweet that the sugar would keep you wide awake throughout your hangover. When I got back to Belgium the next year and started following a generic wine class, Beaujolais was never really mentioned in a positive way. It always came across as the region that had its chance at success but never got it quite right, ruined by quick gains and a marketing machine in overdrive.

When we moved to Brussels last year I rediscovered the wines of Beaujolais. By then I had was becoming more and more intrigued by the natural and/or biodynamic wine movements, so a new venture into Beaujolais was inevitable. The logical first step was Marcel Lapierre, who was one of the most important proponents of the new way of making wine in the region (he passed away in 2010 but his son and daughter now run the domain). Instead of trying to appeal to the masses, using all available techniques and additives possible in order to find something that was so uniform in flavour that everything would like it, Lapierre and several other vignerons wanted to be different, they wanted to express the terroir through their wines.

Up until the Second World War, Beaujolais Nouveau was a regional tradition, a celebration of the new vintage. Powerful négociants like Georges Duboeuf saw the potential in easy-drinking fruit-driven wines that had such a short shelf life that you had to drink half a bottle in the store already. Exports rose exponentially and every year people all over the world (most of them in Japan though) would bathe in Beaujolais Nouveau, gallons would be used in fountains and everyone wanted to be seen with it but no one actually drank it. The effect on the region was economic growth at first, but soon every winegrower was assumed to produce only Beaujolais Nouveau and nothing else. Now, if you had to ship millions of bottles in such a short period of time, you need a lot of wine. This could only be achieved through pushing yields to the limit, using artificial yeasts and sulfuring the hell out of the wines to prepare them for export.

Marcel Lapierre is without a doubt the most famous of the five, but others like Foillard, Thévenet, Métras and Breton were essential in changing the way people see Beaujolais. Minimum intervention in the vineyard, avoiding the use of pesticides and herbicides, minimizing the use of additives and sulphur (or abandoning it completely in several cases) are the ground rules of the new way. The new movement of winegrowers showed the world that there was more than bubble-gum and banana aromas and managed to get back to the essence of Beaujolais: offering pleasure.

Marcel Lapierre is without a doubt the most famous of the five, but others like Foillard, Thévenet, Métras and Breton were essential in changing the way people see Beaujolais. Minimum intervention in the vineyard, avoiding the use of pesticides and herbicides, minimizing the use of additives and sulphur (or abandoning it completely in several cases) are the ground rules of the new way. The new movement of winegrowers showed the world that there was more than bubble-gum and banana aromas and managed to get back to the essence of Beaujolais: offering pleasure.

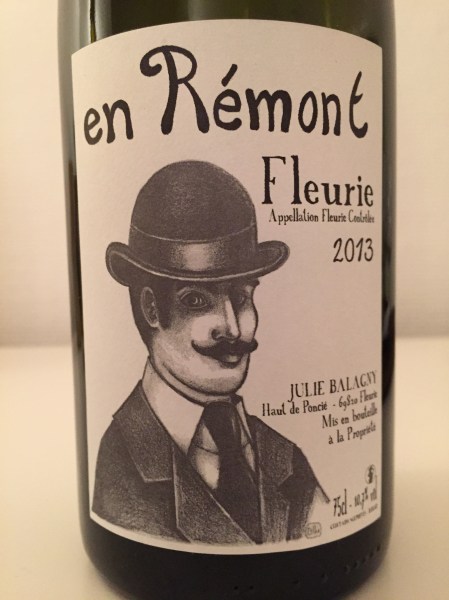

True Beaujolais is not a wine that you buy for complexity, it is not a wine that you analyze until you have discovered twenty different kind of spices, flowers or coffee, it is the kind of wine that simply offers you pleasure and enjoyment with every sip. I bought my first bottle of Lapierre’s Morgon 2013 a couple of months ago and gave it a relatively simple tasting note: juicy, pure and utterly drinkable. Mind you, it did not have the earth-shattering effect it seems to have on a lot of natural wine aficionados but it was up until that point one of the most enjoyable wines to have crossed my path. True Beaujolais is irresistible. Even now I am sipping what I have left of a recent tasting (Julie Balagny’s En Rémont 2013) and I just can’t stop, it is that delicious. People need to rediscover what pure joy in a glass can taste like and I have to confess that I am a convert, preaching the Beaujolais gospel. It can be one of the greatest wines to enjoy with just about everyone.